The feeling that everything in the Church had to go down was the first thing that broke that sentence of the inaugural speech of the Pontificate: "Do not be afraid, open the doors to Christ." (22-X-1978). The call was not widely noticed or understood at the time, but it proved to be a turning point in the downward trend of the post-conciliar era and opened a horizon of hope and youth, which would develop over the next 26 years of the pontificate. The phrase was to become the motto of the pontificate, as the hymn underlines Non abbiate paura, that Marco Frisina composed for the beatification.

With these words, somewhat solemn and poetic, as he liked, John Paul II addressed, first of all, the political and economic systems, especially the Marxist societies, but also the liberal ones, to ask them to accept the message of Christ. It was the program of the pontificate: not to be afraid to propose the salvation of Christ, the Gospel, to all men. To be clear about its value and, therefore, about the mission of the Church, its strength and its justification in the modern world. It was also the justification of his own mission in the world, that of the Pope, who is not just a venerable remnant of past eras that attracts tourists to Rome, like the Vatican Museums or the Roman Forum. John Paul II felt that he was the depositary of a mission, that of the Church with its message for all peoples, and with the renewal and urgency that the Second Vatican Council had given him. He was accompanied by a conviction and health that underlined his proposal. Later, he lost his health, but he did not lose his conviction.

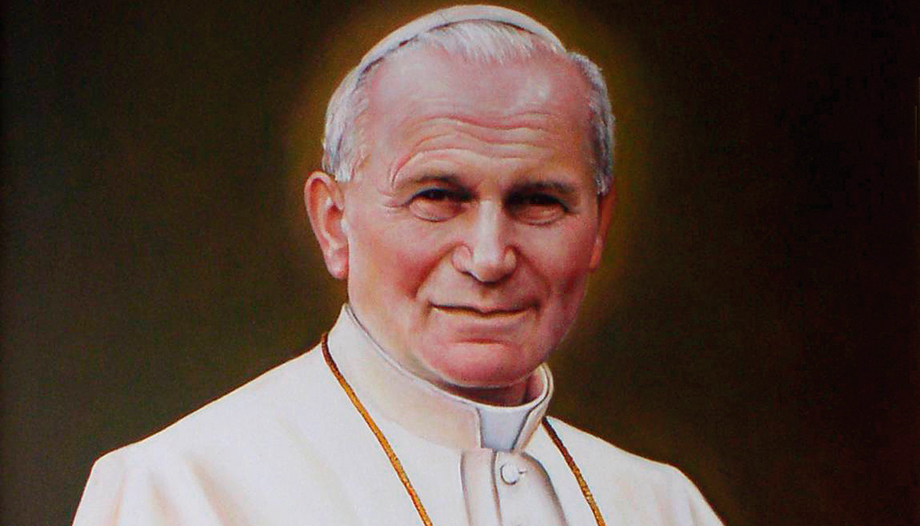

John Paul II was elected Pope on October 15, 1978, at the age of 58. He was in his prime, strong, sympathetic and determined. He came from a Poland that was then very separated from the rest of Europe by the Iron Curtain, and under a clear and severe communist domination. Perhaps that is why he was not on the list of "papables". I remember that, when Cardinal Felici pronounced his name in St. Peter's Square, no one knew who he was and his photo was not in the newspapers. Moreover, since he tried to pronounce Wojtyła with a Polish accent, with the barred "l" being a "u", the name could not be recognized in the lists. Next to me, someone commented that it must be Swahili and searched through the African cardinals. The election was a total surprise and every subsequent step a new surprise: the gestures, the themes, the style, the proposals. In almost 26 years he did not stop and did not let it stop.

Who was

Although he was not among the favorites, he was known to the cardinal electors and some had taken notice of him. He had shone at the recent synod on evangelization and catechesis. He had helped to draft the encyclical Humanae vitaeHe had preached the Spiritual Exercises to Pope Paul VI (1968), and had defended it in various conferences around the world. And he had preached the Spiritual Exercises to Paul VI shortly before (1975). There is talk of the promotion made to him by the then Cardinal of Vienna, Franz König.

He certainly had an interesting profile. He had participated in the making of Gaudium et spes of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1964), despite being one of the youngest bishops. He had a strong intellectual formation and inclination, being a professor of ethics in Lublin, and having promoted several magazines of Christian and personalist thought. But he was also a pastor in a difficult situation and had promoted the pastoral care of Krakow, in the midst of a communist regime. Those in the know knew of his intervention in difficult issues of the Church in Rome. He knew how to move in public. He was not shy at all. Moreover, he had natural gifts of sympathy, decisiveness and capacity for dialogue. He had an amazing capacity for languages. He could converse in French, English, German, Spanish and Italian, in addition to his native Polish. And he loved it.

A long and intense pontificate

From the beginning, it was a surprise in terms of style and initiatives. The style came from within him. Popes change their name to express the new status they acquire. Karol Wojtyla changed his name, but he assumed his mission, without ceasing to be himself. On the contrary, he was sure - he wrote it - that he had been chosen to develop what was inside him. What pope would have dared to write such personal books about his life and thought as: Crossing the threshold of hope; Gift and mystery; Get up, let's go; y Memory and identityin addition to the poems?

These were not personal occurrences. He had had to live in his flesh many crossroads of the Church in history. He had had to live under the totalitarian Nazi and communist regimes, he had had to explain to young people the morals of the Church, especially sexual morality, and he had had to seek paths of personal conscience in his university teaching of ethics and morals. In addition, he had had to defend Humanae vitaeThe idea of sexuality and the human being, a Christian anthropology, was implied in a way that implied a Christian anthropology.

His poise, based on strong convictions and faith experiences, proved immensely valuable at a time of uncertainty. He entered into all the difficult questions, one after the other, with a patience and tenacity that was truly astonishing and characteristic of his character. And, at the same time, with a characteristic ease. He was not a tense man. He gave himself time to study and have matters studied and he liked to discuss them. This could delay them, but they came to port one after the other. One need only think of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. When it was proposed, many thought it was an impossible task.

He was not afraid of thorny issues. He faced many of them, well aware of his mission. He brought together bishops from countries going through difficult times or congregations in trouble. He intervened in major international issues and multiplied the Vatican's diplomatic activity on behalf of peace and human rights. This, in parallel with a great number of doctrinal initiatives, constant travels and visits to the parishes of Rome and the Italian dioceses. Because he was also Bishop of Rome and Primate of Italy.

He was a clear protagonist in the dissolution of communism in Eastern Europe. That was as miraculous as the fall of the walls of Jericho, although it also involved a conscious and intense diplomatic activity and a determined and explicit moral support to his fellow countrymen in the union. Solidarity. A support that was not emotional and opportunistic, but based on the principles of social justice and human dignity. And it earned him an attack that clearly made him a sharer of the cross.

He proclaimed again and again the moral principles and their practical applications (defense of life and family, social doctrine, prohibition of war), whether or not they were politically correct. He resolutely opposed the Gulf War. He stood up to the Sandinista and Castro regimes, and channeled liberation theology. He had the Galileo case thoroughly investigated. To prepare for the change of millennium, he wanted to purify the historical memory and asked forgiveness for the failures of the Church and the sins of Christians. He wanted greater transparency in Vatican affairs. From the beginning, he promoted ecumenical dialogue with Protestants and Orthodox. And he made unprecedented gestures with the Jews, whom he sincerely appreciated, and also with the representatives of other religions, whom he gathered to pray together.

A style and a conscience

As much as his mood, his poise was striking. Any conscientious authority feels the weight of his office. For this reason, he also needs to keep his distance. John Paul II never rested from his office. He always wore it. He exercised it day in and day out, in front of the whole world. He regularly had guests at his morning Mass and at his table, breakfast, lunch and dinner, as well as multiple audiences. He constantly sought to meet people and often skipped protocol, quite naturally. He was not a curial man and was not attracted to paperwork. This he entrusted to his subordinates. And there, perhaps, some things escaped him.

He was convinced that his mission was to transmit the Gospel as what it is, a personal testimony, and that he had to do it united to the whole Church. Hence, the importance of the trips and convocations, which, at the beginning, seemed an anecdote and, nevertheless, constitute one of the keys of the pontificate. He gathered millions of people to pray, to listen to the Gospel or to celebrate the Eucharist. Some rallies were the largest ever recorded in human history. But more importantly, this was a privileged exercise of his papal ministry and produced a visible impact of unity and renewal throughout the Church at a difficult time.

The principle that the Eucharist builds the Church was fulfilled before all eyes. After so many divisions and uncertainties, the Church gathered on all continents around the successor of Peter to manifest her faith, celebrate the mystery of Christ and increase her unity in charity. Many bishops and priests regained hope, joy and the desire to work. The testimonies are innumerable, in addition to arousing a wave of priestly vocations.

A man of faith

He gave a constant and natural witness of piety and faith. Everyone saw him speak with faith in the doctrine of the Church, with faith also in the documents of the Council, in which he saw the path of the Church that he had to follow. He had a doctrine that had matured in depth, with his intellectual mind concerned, since he was a university professor, to establish an evangelizing dialogue with the modern world. He also had pastoral experience and a clear concern for young people and their concerns. From there he conscientiously developed the Christian matrimonial and social doctrine. And the relationship between faith and reason.

He was seen praying continuously, year after year. This was especially true for those who lived close to him in the different stages of his life, who left a unanimous testimony and countless anecdotes. When so many times they saw him in the chapel during the nights of those exhausting journeys. First of all, Pope John Paul II governed the Church by praying. He was not a manager of ecclesiastical affairs. He did not seek efficiency in the office, but in the chapel. He was seen celebrating the Eucharist with intensity and concentration in Rome, in private and in public. He was seen by millions of believers in his travels and on television. Especially in his joyful encounters with hundreds of thousands of young people from all over the world.

He was also seen to go personally, with his characteristic poise and awareness of faith, to international forums and also to dialogue with the great authorities of the world, to propose the faith of Jesus Christ, with the conviction that it is a savior for all men and all cultures. He was seen to oppose all wars and all violence, and to defend human life from beginning to end, and human dignity in all circumstances. All this has been history, and it was made in the sight of all.

He left a remarkable amount of documents, covering all aspects of the life of the Church. He left a Catechism, which is a milestone in its history. And the renewed Code of Canon Law. He left many luminous personal writings. And, above all, the personal imprint of a man of faith and prayer. And he fulfilled the mission that he himself believed he had assumed, with his providential conscience, to enter with the Church into the third millennium, "crossing the threshold of hope".