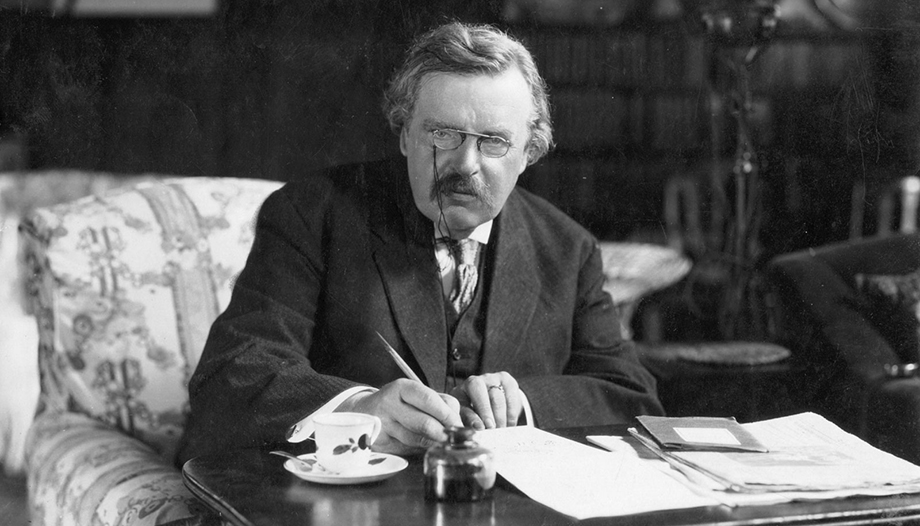

In the summer of 1922 G. K. Chesterton finally knocked at the doors of the Catholic Church. He was then 48 years old. He was to be received into the Church on Sunday, July 30, in a room of the station hotel used as the parish headquarters in Beaconsfield, just outside London. At communion he was very nervous and sweat covered his forehead: "It has been the happiest hour of my life" (The man who was Chesterton, p. 207). To speak of Chesterton's conversion is to speak of a journey from confusion to lucidity. Along the way he rediscovered fairy tales, enjoyed his brother and his friends, was amazed by the magnificent priests of the High Church - the most pro-Catholic and ritualistic group in the Anglican Church - and fell in love with his wife, Frances Blogg.

Everyone knows that Chesterton was a witty apologist for the faith, who came up with some amusing stories about a priest-detective and also a rather odd novel called The man who was Thursday. Few know, however, that Chesterton, far more than an apologist, always called himself a journalist, that Father Brown is inspired by the priest who confessed to him that summer of 1922 and that The man who was Thursday illustrates the nightmare that Chesterton lived as a young man, before finding God.

Road to faith

That nightmare runs like a shiver through the year 1894, when Chesterton was 20 years old, had no belly and wanted to be a painter. At the prestigious Slade School of Art in London he managed to master the arcane technique of idleness and dabbled without judgment in the various occurrences of his time, such as doubting the existence of everything outside his mind. "And the same thing that happened to me with mental limits, happened to me with moral ones. There is something truly disturbing when I think of the speed with which I imagined the craziest things. [I felt an overwhelming urge to record or draw horrible ideas and images, and I was sinking deeper and deeper into a kind of blind spiritual suicide. At that time, I had never heard of confession in earnest, but that is precisely what is needed in such cases." (Autobiographypp. 102-103).

Until he had enough: "When I had already been plunged for some time in the depths of contemporary pessimism, I felt within me a great impulse of rebellion: to dislodge that incubus or to free myself from that nightmare. But since I was still trying to solve things myself, with little help from philosophy and none from religion, I invented a rudimentary and provisional mystical theory." (p. 103). The cornerstone of that elemental mystical theory was gratitude. Chesterton realized that everything might not exist, he himself might not exist. The inventory of things in the world was then an epic poem about everything that had been saved from shipwreck. Chesterton held on to that fine thread of gratitude and years later, in 1908, he would illustrate that discovery of his in Ethics in the Land of Elvesthe fourth chapter of his Orthodoxy.

Chesterton wished to recover the clean look of children, the simplicity of common sense. So in the theory he invented he was only interested in ideas that would restore him to health. Later he realized that besides being healthy, his theory was true. In his excursion towards the light, he stumbled upon Christianity: "Like all serious kids, I tried to be ahead of my time. Like them, I strove to be ten minutes ahead of the truth. And I discovered that I was eighteen hundred years behind. [...] I strove to invent a heresy of my own and, after putting the finishing touches to it, I discovered that it was orthodoxy." (Orthodoxy, p. 13). When he awoke from his nightmare it was around the year 1896. He awoke to the astonishment that life is an adventure suitable only for humble and free travelers, an epic with a meaning and an Author.

A great wife

At a debating club in the fall of 1896 he met Frances Blogg, the woman who in 1901 would become Frances Chesterton. With her help he was able to trace the acrobatic leap from his intuitions to the consistency of the Catholic faith. Frances was a poetry-loving intellectual. Her family was agnostic and she was Anglican. She was to be received into the Catholic Church in November 1926, so she took the same path of apprenticeship as her husband. But she helped him because she familiarized him with devotion to Our Lady and gave order and concert to his life. She would pick up where he scattered: "He buys train tickets, calls the cab to take him to the station, screens phone calls, hires a secretary, tidies up papers and books..." (The man who was Chesterton, p. 91).

Chesterton and Frances were unable to have children. But Frances hired a secretary, Dorothy Collins, with whom they formed such a strong bond that they adopted her as their daughter. There Frances and Dorothy were, around Chesterton's bedside, when he died on Sunday, June 14, 1936.

With his sense of humor and boyish eyes, he left a luminous legacy as a defender of the faith. However, perhaps Chesterton would not have liked to be called a "Christian intellectual". He would have been uncomfortable with the pretensions of an intellectual or he would have blushed because, with great humility, he only wanted to get rid of his sins. Although he loved to fight, even with toy swords, he would not have engaged in sterile cultural wars of Christian intellectuals. He would have always found in polemics a good occasion to make friends, laugh out loud and toast with burgundy.