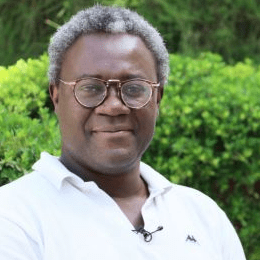

A few weeks ago we celebrated the World Day of the Poor and on October 20, Manos Unidas held a round table to talk about hunger in the world. Fidele Podga, coordinator of the Department of Studies and Documentation of Manos Unidas, was the speaker. Manos UnidasIn an interview with Omnes, he spoke about this problematic situation that is spreading across the globe.

-A few days ago, Manos Unidas explained at a round table the current problem of access to food for more than 800 million people. What are the characteristics of this reality that does not seem to be receding?

According to the latest United Nations report, some 828 million human beings are still suffering from hunger in the world today. This is certainly a complex reality, difficult to fully delimit, which takes on different forms depending on people, times and places. All in all, we would say that:

Hunger is a systemic problem, where its structural characteristic undoubtedly stands out.. It is not so much an error or dysfunction of the system, as something inherent to the system itself - especially the current food system - organized around: the fragility of States marked by corruption and flows of illicit funds; the scarce investment for the most needy through sustainable family farming; the defense of a food market economy that puts agricultural resources in the hands of transnational consortiums, practices dumping to weaken local markets; benefits from export subsidies for agricultural products from rich countries, or imposes the elimination of tariffs in developing countries.

Today, hunger has also become contagious; it is a hereditary scourge.. Indeed, we know that malnourished families give birth to children with mental and physical disabilities, who will later become malnourished adults, giving rise in turn to a new malnourished childhood. Just as wealth can be inherited, hunger can also be inherited, thus giving rise to another vicious circle with serious consequences for individuals.

Hunger also has a cyclical dimension. It is especially rural populations who have the greatest difficulty in feeding themselves. We know that they still depend on an agriculture that is very vulnerable to climate change, the phenomena of which, unfortunately, are often recurrent. Thus, when rainfall is insufficient or when there are floods, there are no harvests, and if there are no harvests, there is hunger. We know where these adverse weather events occur with some regularity: Central American Dry CorridorThe right to food is not always guaranteed in these areas: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, or the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Unfortunately, little is being done to guarantee the right to food in these places.

Hunger is also presented as a cross-cutting phenomenon.. Although it is certainly unequal, hunger affects all countries, especially their most vulnerable groups. That is why the 2030 Agenda itself proposes, without exception, "By 2030, to end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including children under one year of age, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round."

Hunger is also feminine, not only as a word, but also because it has the face of a woman.. They always eat last, after they have fulfilled their heavy responsibilities of caring for fields, home and family. Nearly one-third of women of reproductive age worldwide suffer from anemia, partly due to nutritional deficiencies.

-We can think that there have been wars, climate problems, etc. throughout the history of mankind. Why is this food problem increasing and worsening in the world?

We will not now fall into the temerity of saying that wars or climate change do not have a real and serious impact on hunger figures.

We know that in many countries where open or latent conflict continues (Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Sudan, Syria, Nigeria, Yemen, South Sudan, Pakistan or Haiti, to name a few) food production, availability and access to food is severely compromised.

On the other hand, climate change undoubtedly has a logical impact on food security, especially on agricultural yields in different regions and types of crops. Extreme phenomena, such as droughts, floods and hurricanes, or the contamination of water and land suitable for agriculture, have consequences for malnutrition. But clearly, these causes alone cannot justify the existence of 828 million hungry people in the world today.

To understand the progress and seriousness of this scourge, I believe it is essential to look at the world food system that is dominant today.

It is a system fundamentally characterized by the commodification of food. In this line, Pope Francis said in June 2016 in Rome at the headquarters of the World Food Program: "Let's be clear, the lack of food is not something natural, it is neither obvious nor evident. That today, in the 21st century, many people suffer from this scourge is due to a selfish and bad distribution of resources, to a 'commodification' of food".

The great increase in hunger has to do above all with the existence of a select group of large corporations that control the entire global food chain, making big business with the sale of agricultural inputs such as seeds, chemical fertilizers and phytosanitary products; getting as rich as possible with an agricultural production directed in part to livestock and fuels, based on the overexploitation of natural resources, land grabbing and the use of cheap labor; controlling global markets, with price control systems, speculative mechanisms or dumping techniques; benefiting from a great financial capacity both with subsidies and various investment funds.

In this context, small farmers in rural areas, trapped in the vicious circle of export agriculture, are practically condemned to starvation. Excluded from the system, they can do little to live with dignity in the global markets thus designed.

The problem that Manos Unidas points out is not the lack of food but the lack of access and distribution of food. So, is there a real social and political commitment to eradicate hunger?

There are still important sectors that link hunger with the need to increase world agricultural production. But the data disprove this. Current agricultural production would be enough to feed almost twice the world's population. However, in addition to feeding cars and livestock, we have full stocks and throw away a third of production. Therefore, the problem is not one of production but of access and distribution; and in these matters there is a clear lack of social commitment and political will.

It is clear that if civil society - especially in the North - were to reduce, for example, its overconsumption of beef, this simple fact would have a major impact on the current dominant food system, both in terms of less pollution and more agricultural land available for the hungriest communities in the South. Likewise, a greater political incidence of the civil society of the North could avoid the inaction of the national and international political class on issues such as corruption and illicit financial flows, equity in free trade agreements, the question of due diligence for multinationals, the control of monopolies and speculation mechanisms, minimum prices for agricultural exports, the subsidization of family farming, etc.

-Some may argue that "ending world hunger is a utopia. Is it? How can we begin to eradicate this terrible inequality?

Hunger is certainly a very complex scourge that is destroying the possibilities of a dignified life for millions of human beings on our planet. But ending hunger is not a "utopia". It is possible. Back in 2015, when talking about the 2030 Agenda, and specifically SDG2, the then United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon said that "We can be the first generation to end poverty".

Technically, ending hunger is feasible. Politically, there is a roadmap, the 2030 Agenda, that could help. But there is a lack of a sense of justice and equality, as well as sufficient socio-political courage, to confront those who continue to consider food as just another financial asset and have designed a global food system for that purpose.

There is no magic bullet to end hunger. But we could approach this great challenge from Education for Development as a space to transmit to society our conviction that hunger is an attack against the dignity of every human being, also proposing lifestyles of solidarity and responsible consumption, capable of confronting this scourge.

Likewise, the fight against hunger today requires a firm commitment to agroecology within the framework of family farming which, in addition to being a model that places the production of their own food in the hands of small farmers, is a way of conserving nature, of promoting a local and solidarity-based economy, of maintaining indigenous cultures and diets, of strengthening community ties within the different territories.