Naturally, after the Ascension of Jesus into Heaven, the Church became continuously concerned about all the problems that mankind is experiencing, especially economic ones. In Spain, it is enough to recall what, in relation to credit and the justification of charging interest rates, gave rise to a wide-ranging debate that developed, in large part, around the University of Salamanca.

But everything related to economics underwent an extraordinary change in the passage from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, as a result of what emerged precisely then, and from a multitude of points of view. In the scientific field, it is evident that the great revolutionary was Adam Smith, who precisely always placed himself outside theological matters, and that in his biography does not seem to have worried him, perhaps as a consequence of the chaos originated in Scotland from the Puritan revolution, which made it difficult to maintain personal religious attitudes.

Let us remember, moreover, that all this would be linked to the birth of secret societies, and of an intellectual diffusion that refused to follow the advice of the Papacy. And this economy, which was born with all these simultaneous complements, came to guide the general development in two spheres: the British, with regard to the Industrial Revolution -an extraordinary novelty-; and, on the political and social side, the French, with the success that the Revolution ended up having.

And, as a result of continuous links between these novelties, the new reality is created, which is added to an extraordinary scientific progress; from mathematics, to physics or biology, a novelty that also affects what happens in the field of the work factor. In the latter, resistance, even violent, soon appeared to messages that, before attracting powerful attention, generated a shudder. As an added consequence, social indignation had come to have an important scientific support with the singular figure of Karl Marx, so that, in addition, historical materialism was not exactly walking along paths suitable for Catholicism.

Rerum Novarum

Moreover, in Europe, a set of nationalisms that sought doctrinal support far removed from what theology had sustained, was taking root. Add to all this a new political fact: Italy had been born, as a joint and independent nation, with basic approaches radically opposed to the Church, due to the existence of the so-called Papal States, which disappeared by war and the Pope became a prisoner, in Rome, of the new political regime born there.

Faced with this panorama, Leo XIII arrived at the Papacy, seeking some kind of arrangement different from that which, for example, in Spain, through the war, had been sought by Carlism from its Catholicism. It was necessary to react against this variety of enemy situations, and that was the logical justification for Leo XIII, in order to establish the message of the Church in the midst of those novelties, to launch an encyclical with a very significant name, because it was necessary to react against that set of situations, even very hostile ones. To this end, from the philosophical point of view, points of support were sought, on which the encyclical was based. Rerum Novarum

Little by little, Rerum Novarum found that, on the one hand, there was a strong advance in economic science, especially from the point of view of microeconomics, with contributions as notable as those of Walras and Pareto. We then saw the consolidation of a great British economic science - it is enough to think that, for example, nothing less than the son of a Spaniard, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, contributed notable innovations - not to mention a series of great economists who traveled to glory in a certain great vehicle, later described by Schsumpeter.

On the other hand, this growing group of great economists developed their science in a truly colossal way. And heterodox lines were also emerging from it. Specifically, the search for a new way to resolve the social question created the corporatismThe Catholic Church, which took root in a multitude of conservative political approaches, and which, at the same time, viewed Catholicism with sympathy.

Quadragesimo Anno

This last general atmosphere met with an important political fact: the Pope had been liberated, from the political point of view, with the Lateran Treaty, developed by Mussolini, who, in turn, in order to stop advances derived from Marxism, found it satisfactory that the path of corporatism existed for this purpose.

Without all this, it is hard to understand that this new Pope, Pius XI, with an encyclical already quite a distance away from the Rerum Novarumpublished with notable success the Quadragesimo Annowhich was intended to be the projection of a new situation much more recent than that of Leo XIII.

Remarkable advances of various kinds had been made in economic science. Since Cournot, microeconomics had progressed in the analysis of monopolistic situations, and this had finally advanced through the terrain of the theory of imperfect competition.

The progress of Economic Theory was colossal, and the linking of corporativism with economic nationalism and protectionism led a whole gigantic group of researchers to point out that this path would inevitably lead to a precipice that would liquidate whoever followed it, when falling down it, no matter how popular its leader was, as was the case then of the Romanian Manoilescu. But the roots of the Catholic Church, in a multitude of intellectual aspects, with this line, seemed to consolidate. It is enough to point out, in Spain, all that the Jesuit Father Azpiazu developed in numerous works, courses and polemics.

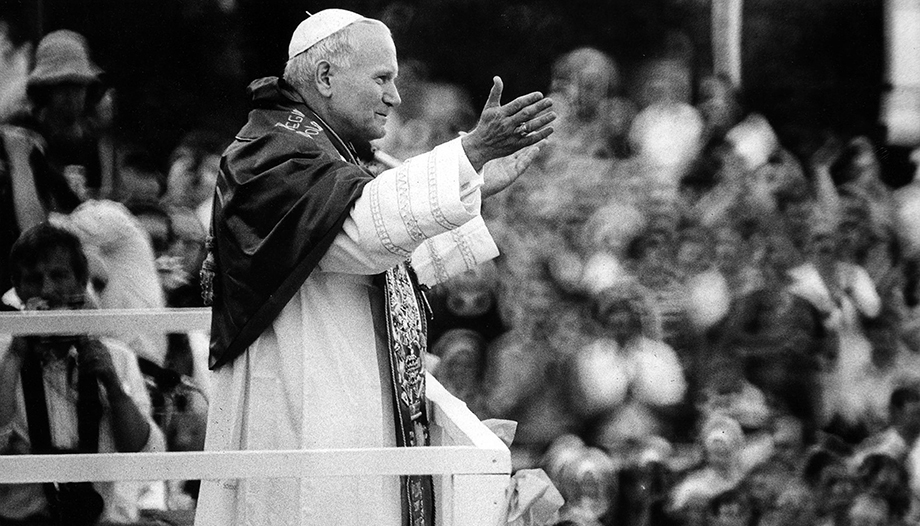

Saint John Paul II

The political links derived from corporatism during World War II were combined with a remarkable progress in macroeconomics, through models that allowed to guide, at any time, the directors of economic policy.

The change became radical in economic science, and the same is true of the political context, which seems to be linked in some way - at times even very strongly - to the encyclical Quadragesimo Anno. Hence the extraordinary courage of St. John Paul II, to make an extraordinary leap on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Rerum Novarum.

In this regard, it is worth noting an event. St. John Paul II perceived the remarkable progress of economic science and how this had repercussions in a triple sense. In the first place, to promote economic development, very visible throughout the European world not linked to communism, and also in those extensions of the Western world that existed, from the United States or New Zealand to Japan. But a variant also arose within the Church in the Ibero-American world, which was given the name of Liberation Theology. The scientific basis was found in the so-called Latin American economic structuralismThe government, which considered itself a radical enemy of the economic approaches triumphant in the aforementioned world of Europe, North America and Japan, considered it necessary to carry out an authentic political and social revolution full of heterodox nuances, which logically alarmed Rome. And at the same time, they considered it necessary for him to carry out an authentic political and social revolution full of heterodox nuances, which logically alarmed Rome.

A meeting at the Vatican

In view of this situation, a radical change took place, of which I learned a great deal during a long conversation in Madrid with Amartya Sen, a great economist who won the Nobel Prize for Economics and has just received the 2021 Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences. Amartya Sen told me that he was astonished, in the field of economics, by the Pontiff's call for a joint meeting to be held at the Vatican.

Practically all those invited, leaving aside their own religious ideas, considered that they should attend the meeting. The list of distinguished guests ranged from Kenneth Arrow, who had won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1972, to Anthony Atkinson, a distinguished professor at the famous London School of Economics and Political Science, to Parta Dasgupta, from Stanford University; it also included Jacques Drèze, from the Catholic University of Louvain, who had a great influence on the training of prominent Spanish economists, without forgetting Peter Hammond, also from Stanford University.

But Harvard University could not be absent, with the presence of Henrik Houthakker; nor could Chicago University, with no less than Robert Lucas; and, from Europe, a member of the College of France, the great Professor of Economic Analysis, Malinvaud; Horst Sievert, from the famous Institute for World Economic Studies in Kiel; Hirofumi Uzawa, from the University of Tokyo; and also, in the existing list was the then Professor Amartya Sen, from Harvard University. Economists from important teaching centers in Italy and Poland also attended the meeting; no Spaniards were invited.

Centesimus Annus

Amartya Sen pointed out to me that they all met in discussions on key points, which were to be noted by the Pope and several senior clerics, for inclusion in the future encyclical, which would be the Centesimus Annus.

To this end, they discussed at length orientations, concrete phrases, appropriate points, continually guided by the Pontiff, in relation to matters of great importance, which almost forced them, at times, to engage in intense polemics; but who also with irony, and with much sympathy and sharpness, participated in the colloquies and guided valuable solutions, was the Holy Father himself. Amartya Sen never ceased to praise me for his reactions and his intelligence. He also emphasized the birth of the opening of the free market economy, which, from that debate, was to be transformed into a very valuable text.

A sample of the general tone praised by Amartya Sen can be found in a letter by Robert Lucas, where he pointed out that St. John Paul II consistently maintained that "underdevelopment depends as much on the precariousness of Civil Rights as on economic errors", and that he also pointed out to the whole meeting that he was not "a connoisseur of technical works on economics, nor did he feel that the Church's duties included prescribing technical solutions to economic issues"; But in the encyclical that was being prepared, it was necessary to contemplate the links that should exist between the Church's social doctrine, the special disposition of each Pontiff and the world of the 21st century, with all its controversies.

This explains why, in contrast to the aforementioned doctrine, called the Liberation TheologyIn the encyclical there is clearly stated the admission of capitalism as a consequence of the free market economy. The text of the encyclical was as follows: "If by 'capitalism' is understood an economic system that recognizes the fundamental and positive role of commerce, the market, private property and the consequent responsibility for the means of production, as well as free human creativity in the economic sector, the answer will certainly be affirmative.... Now, if by market capitalism if we understand a system where the freedom of the economic sector is not contained by a firm legal framework that places it at the service of human freedom in its totality, and conceives it with a particular aspect of that freedom, the core of which is ethical and religious, then the answer will be clearly negative". The link with the thesis born by a group of German economists and which has been given the name of social market economywas very clear.

In this way, the link with orthodox economic science shines through, and if we look for the right moral conduct for a serious economic policy in St. John Paul II, we have it, as Amartya Sen insisted to me in his very complimentary conversation. For this reason, he deserves a special applause from Catholics, not because he is a Catholic, but because he deserves to receive the 2021 Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences in Oviedo.

Honorary President of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences